Learning How To Learn

If you’re a little bit like me, some subjects could seem too complicated. Other times you’d find it very hard to get started with something and keep procrastinating it. Or you might find yourself very tired to learn something new. And frankly, if we overcome all these we might find it was all in vain and we forgot most of it. Let’s fix this!

It’s mostly a thing of having a well-rested brain, a proper mindset and a proper technique to improve your learning a lot.

As part of my “Learning How to Learn: Powerful mental tools to help you master tough subjects” Coursera class I am writing this post. It’s supposed to be a gift that keeps on giving. It helps me master what I learned by repeating the concepts and it will teach someone else concepts that are supposed to be life-changing.

The big picture

Many of us enjoy exploring new interests and learning new things. I think I always did, except maybe for half my life when I was in school 🙂. The school system in my country favored going for the grades and not for the education so pretty much everybody that learned, did it just before getting tested, we got our grades and then we would forget most of it. I used to think that even though in 19 years the school didn’t teach me much, at least it taught me how to learn. But it seems that is not the case either.

Anyways, this is not about school systems it’s about our personal systems. I often need (for making money) or want (for health, hobbies, the sake of others, etc.) to learn more, faster, better and I find myself accomplishing way less than I think I could accomplish. It’s time to get better at learning before we can get better at other things.

The Mindset

Like many of the other things which follow, it’s essential to have the proper mindset. Knowledge is made by people FOR people. We all start as a blank slate. We learn a HUGE amount of things by the time we grasp reading and basic arithmetic. Let’s not stop learaning, ever!

If you read or listen to interesting things which you’d like to learn but you don’t apply yourself in the direction of learning them, likely that will not happen.

Looking at scientific research tells us that most of us think we’re above average. Let’s use this fallacy to our advantage, believe we can learn everything and increase our chances to become above average.

Sleep

When you’re tired you don’t remember. As the day progresses, the brain accumulates substances that interfere with strengthening neural pathways.

During sleep, the brain clears all the substances which inhibit learning.

I highly recommend reading the Why We Sleep book (ISBN 9781501144318). It presents many other advantages to having proper sleep which will also be good for your learning.

Thinking modes

Our brain has two modes of thinking:

- Focused mode thinking

- Diffused mode thinking

In focused mode thinking we can point our mind to e narrow subject, just like a searchlight. It helps us understand that specific thing so we can then store it in memory, thus forming a chunk of information. Focused mode thinking uses a lot of mental energy and it’s not sustainable for prolonged periods. Also, when we’re in focused mode our vision is very narrow and often we can’t clearly see the bigger picture.

Diffused mode thinking is a more relaxed way of thinking when we just let our minds wander. We let the thoughts pop into our minds as they please and it’s often a very good source of general problem-solving and creativity. We can stimulate diffuse mode thinking by walking or doing other relaxing activities that don’t grab your focus. During the diffused mode thinking, the chunks we formed in focus mode interact in a relaxed fashion.

Both modes are very important. Thinking works best by alternating between these two.

Memory

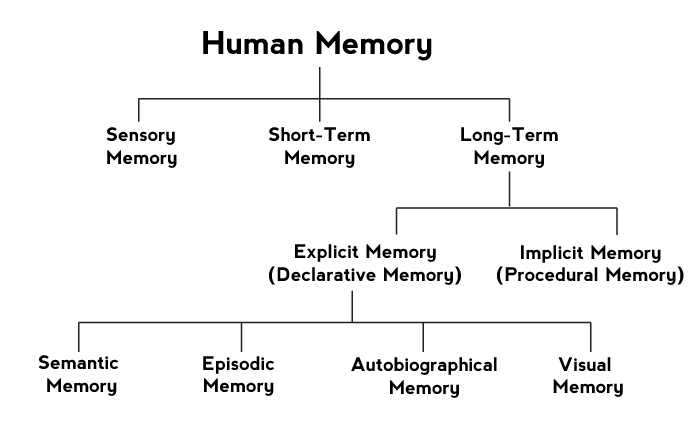

Although our memory is very complex, for the sake of grasping the main ideas as quickly as possible we are going to touch a little on the main two branches, short-term memory and long-term memory.

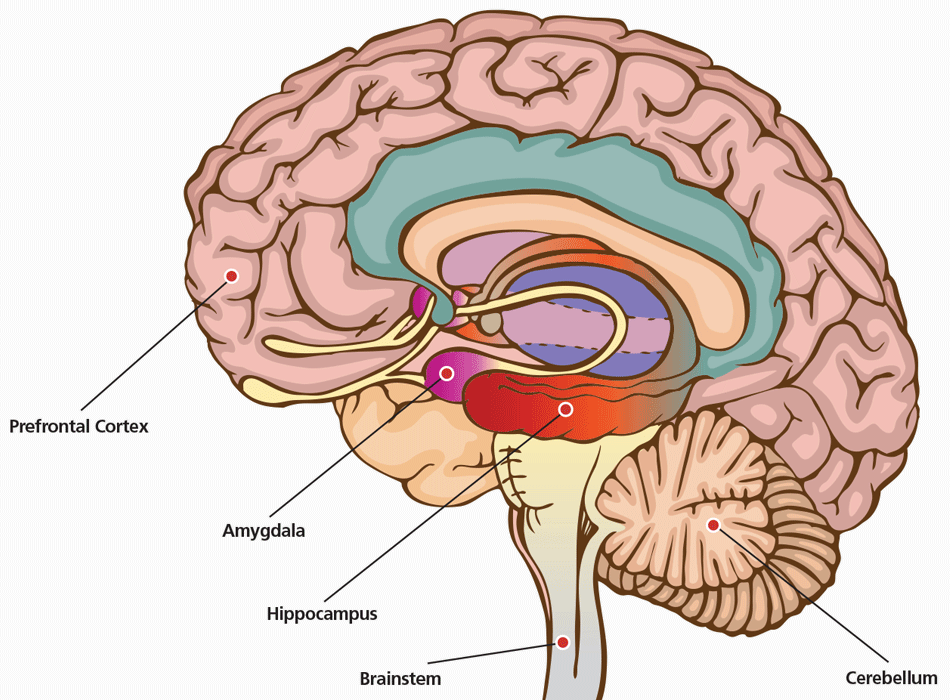

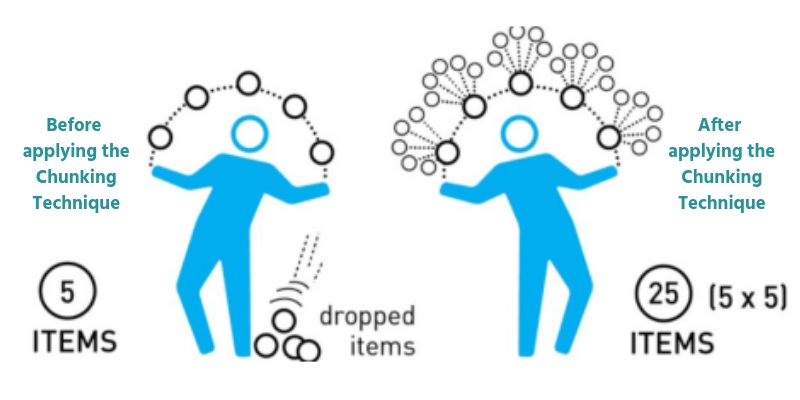

Our short-term memory, often described as working-memory, is handled by our prefrontal cortex and it can only store 4±1 items for just 15-30 seconds, according to Cowan (2001) and Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968). We’re using this memory pretty much for any type of thinking and it’s important to understand its limitations.

This memory is small, easily distracted, and very short-lived. If I am focused on my work and notifications fire on the computer and the phone, they bump items out of my short-term memory. If I actually check out those notifications, the short-term memory gets wiped out and I need to recreate it. This process requires energy and our brain gets tired faster in the process.

When we’re working with chunks of information (pieces that we already have in the long-term memory), they use less space in our working memory. To solve complex problems we first need to develop the necessary chunks.

Long-term memory is VAST. It is comparable to a warehouse where pieces of information stay until they’re needed. Like a warehouse, different areas seem to be used for storing different types of information. Walking, biking and writing are part of our unconscious memory and we call this implicit memory.

Knowledge about factual information, like how you use some software on your computer, is called semantic memory and it’s part of our explicit memory. Semantic memory is subject to fading and we can protect from that through deliberate recall.

Things get into the long-term memory when after the information is manipulated in the short-term memory and then it’s encoded by the hippocampus. Repeating the information activates and strengthens the neural pathways related to that piece of information. If the hippocampus gets damaged you can still retrieve memories but you can’t form new ones. The protagonist of the movie Memento had this problem.

Chunking

As we learn a concept, it becomes a chunk of information and it gets stored in the long-term memory. When we grasp it clearly, this chunk takes only one slot in our working memory.

Our diffused mode thinking interacts with different chunks, sometimes even from different areas of knowledge, to come to a solution for a complex problem.

Spaced repetition

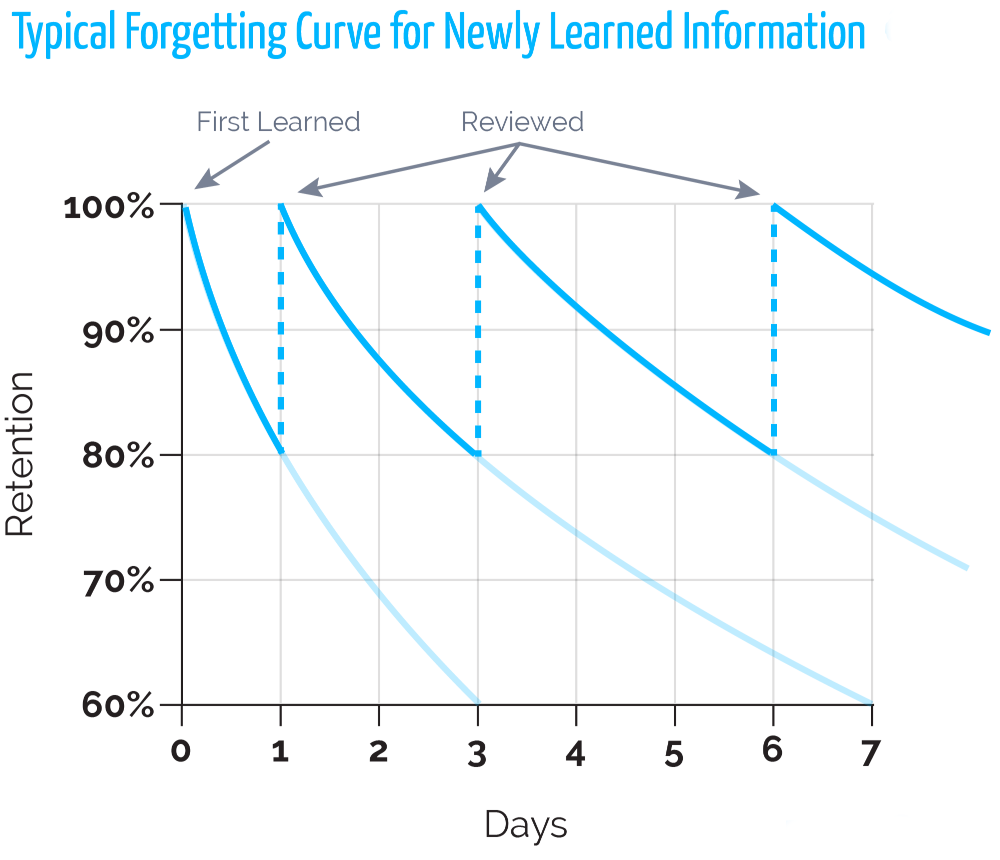

We mentioned before that repeating a piece of information makes it stick. Instead of doing all the work of memorizing in one big session, it’s way more effective to split it across multiple days into much shorter sessions. If you learn the subject at once you’re way more likely to forget it and have a bad day.

This technique of learning was studied multiple times since 1932 and has been proven to increase the rate of learning.

Spaced repetition allows us to be more chill about learning and learn better.

For example, Duolingo, the popular language app employs spaced repetition as the main teaching mechanism. Headway tries to apply this to books. A general-purpose tool for doing spaced repetition is Anki. Let me know if you find something better.

Procrastination

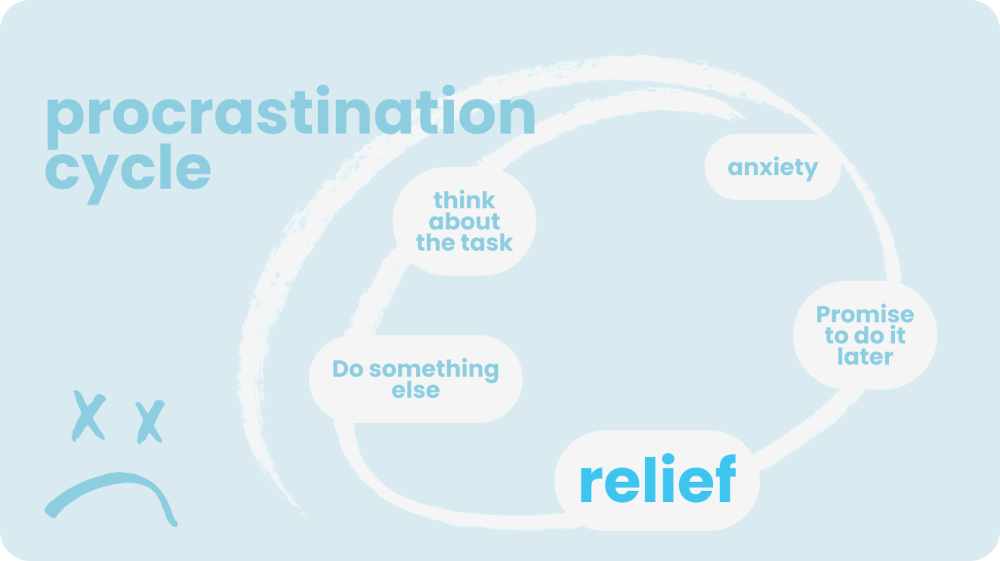

When we think about starting to work on a complex task our brain actually feels pain. Not like skin pain, but brain pain. And it wants to protect itself by changing our attention to something way easier, like surfing on the Internet or talking to other people.

If we get started with our task, the pain goes away very quickly and we can then focus on our task. A notification would break that focus and we’d have to go through that initial pain again. And another problem is that going through this pain uses the limited willpower we have during a day.

There are a few key actions that we can do here:

- Start early with the task that would require the most willpower

- Minimize notifications so we don’t waste energy on overcoming the pain over and over again

- Take deliberate breaks to rest and do diffuse mode thinking

- Treat yourself so that you train your brain that at the end of a work session something good is coming

The most well-known technique for fighting procrastination is the Pomodoro method. Its basic principle is that you work for 25 minutes and then take a break for 5 minutes. After two hours you’ve done 4 pomodoros and you can take a 30-minute break.

The Pomodoro method doesn’t really work for me. I need longer than 25 minutes sessions so I will invent the Rădulescu method. 50 minutes of work and 10-20 minutes of break. It’s not yet clear how many of these sessions I would do in a day but I’ll try different things.

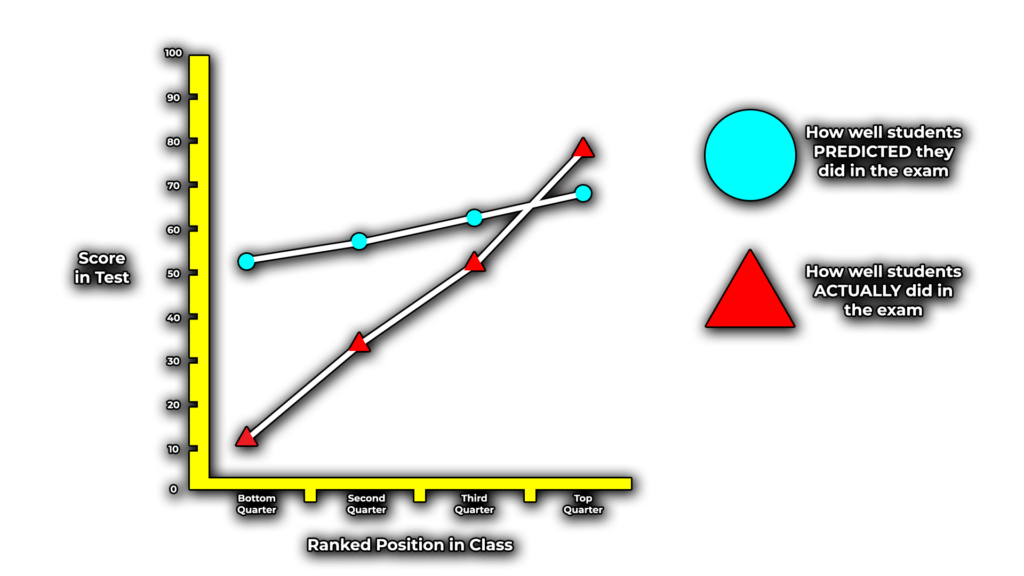

Illusion of competence

If you know how to drive a car and you look at F1 races, you might think you could drive an F1 car. This is a well-known cognitive bias called the Dunning-Kruger effect.

When I started to write this blog post about learning how to learn I thought it was going to be quick and easy. I got 100% on my test so to me that looked like I mastered the subject matter. In reality, I am 5 hours into this and still learning.

You can only know for sure you are competent in a subject when you do it yourself. Test yourself!

What next?!

If you feel it’s worth keeping anything out of this I will give you an assignment. Drop me a message with 3 key points which you think will improve your learning the most. This exercise WILL strengthen neural pathways especially if you go over those key points on different days during a week.

Looking forward to your message!